How often does Rust change?

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how often Rust changes. There are some people that assert that Rust stays fairly static these days, and there are some people who say Rust is still changing far too much. In this blog post, I want to make a data driven analysis of this question. First, I will present my hypothesis. Next, my methodology. Then, we’ll talk about the results. Afterward, we’ll discuss possible methodological issues, and possible directions for further research.

As said on twitter:

The hypothesis

My personal take on Rust changing: to me, it feels like we had more change in the past than we have today. The changes are also getting more minor. This will be my hypothesis.

The methodology

There are tons of different ways that we could measure the question “how often does Rust change?” So before I started collecting data, I had to decide some details.

I realized that my premise here is about how people feel about Rust. So, how do they tend to understand how Rust changes? Well, the primary way that we communicate change to the Rust community is through release blog posts. So I decided to start there.

What I did was, I opened up every release blog post for Rust, from 1.0.0 to 1.42.0, in a new tab. For fun, I also opened the release notes for 1.43, which will come out soon.

I then looked at every single change announced, and categorized them as follows:

- adds syntax?

- language

- standard library

- toolchain

- major

- medium

- minor

I initially included “deprecation” and “soundness” as categories too, but I ended up not including them. More on that later.

From here, I had to decide what these categories meant. What standard would I be using here? Here’s the easier ones:

language changes mean some sort of modification to the language definition. These are additive changes, thanks to our stability policy, but they’re new additions.

standard library means a change to the standard library, primarily, new functions, new types, new methods, stuff like that. This one is pretty simple as a criteria but there’s some small interesting methodological issues we’ll get into later.

toolchain changes related to cargo, rustup, new compiler target support, stuff like that. Not part of the language proper, but part of the Rust distribution and things Rust programmers would use.

Now, for the harder ones:

major/medium/minor changes are how big of a change I think that the change is. There’s a few interesting parts to this. First of all, this is, of course, very subjective. I also decided to try and evaluate these as of today, that is, there are some changes we maybe thought were major that aren’t used all that often in practice today, so I categorized those as medium rather than major. This felt more consistent to me than trying to remember how I felt at the time.

adds syntax changes sound easy, but are actually really tricky. For example, consider a feature like “dotdot in patterns”. This does change the grammar, for example, so you could argue that it adds syntax. But as a programmer, I don’t really care about the grammar. The summary of this feature is “Permit the .. pattern fragment in more contexts.” It goes on to say:

This RFC is intended to “complete” the feature and make it work in all possible list contexts, making the language a bit more convenient and consistent.

I think these kinds of changes are actually very core to this idea, and so I decided to categorize them according to my opinion: this is not a new syntax change. You already had to know about ...

I believe this may be the most controversial part of my analysis. More on this later, of course.

Okay, so that’s the stuff I covered. But there’s also stuff I didn’t cover. I was doing enough work and had to draw the line somewhere. I left this stuff out:

- compiler speedups. This is interesting with numbers, but that means actually compiling stuff, and I don’t have time for that. This is a whole study on its own.

- Documentation work. This tends to be not tracked as new features, but sometimes it appears in release notes, for bigger things. Better to just leave it out. I also don’t think that it affects my hypothesis at all.

- Library types implementing new traits. These can be hard to number, especially with generics involved. I decided that it would be better to leave them off.

- compiler internal news. We sometimes talk about things like “MIR exists now!” or “we ported the build system from make to cargo!” but similar to documentation, we talk about it very little. It’s also not a change that affects end users, or rather, it affects them more directly by stuff that is counted. MIR enabled NLL, and NLL was tracked as a language feature.

The results & analysis

I am not as good with Google Sheets as I thought, so I asked for help. Big thanks to Manish for helping me get this together. I should note that he set me up, but then I tweaked a ton of stuff, so any mistakes are mine, not his. For example, I got a little lazy and didn’t realize that the colors aren’t the same across the various charts. That’s my bad.

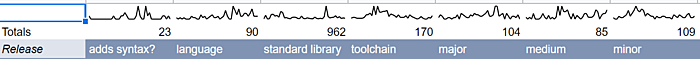

Here’s some quick totals of how many changes and of each kind I found, with some sparklines. You can click on any of the images in this post to enlarge them:

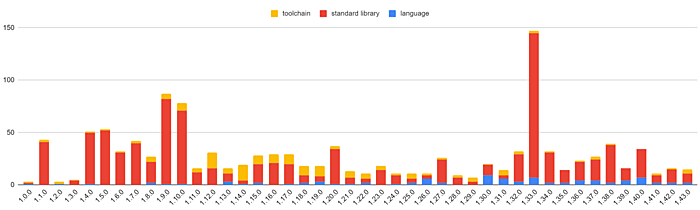

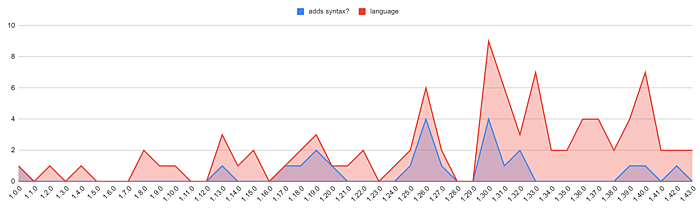

And here’s some charts, per release:

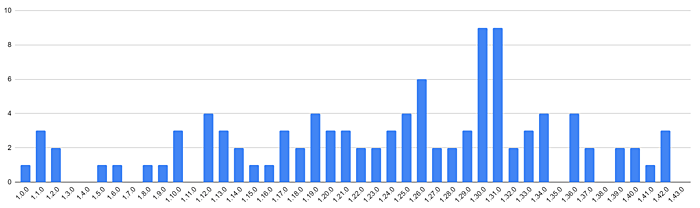

First of all, it is fairly clear that, at least numerically speaking, the standard library is the part of Rust that changes most often. It’s a clear outlier by volume. I find this result kind of hilarious, because Rust is well-known for having a small standard library. We’ll talk more about why I think this is in the “Issues and further research” section below.

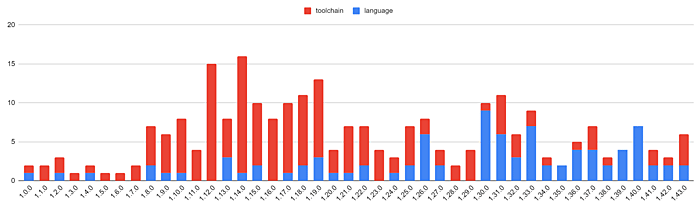

Let’s look at the chart without the standard library:

You can see there’s a ton of toolchain changes early on. We had a lot of work to do early on, and so made a ton of changes! It’s calmed down in recent times, but toolchain changes happen almost twice as often as language changes. I should also note that this reduction in toolchain changes may be due to methodology; this is talked about later in the post.

So, the core question here: it looks like the language is changing more, recently, rather than less. I think it’s pretty clear that this graph is not exactly what I would imagine, that is, I expected a nice gentle curve down, but that’s not what has happened. I want to dig into this a bit more, but first, let’s look at some other graphs:

Changes that add syntax are a subset of language changes. There hasn’t been a whole ton of this, overall. Rust 2018 was the large bump. Half of our releases do not add syntax, though 10 out of 43 did introduce language changes. Our first 29 releases, skipping 1.26, had around one or two changes on average, but every since, it’s been between three and four. I believe this has to do with my methodology, but at the same time, this pretty resoundingly refutes my hypothesis. Very interesting!

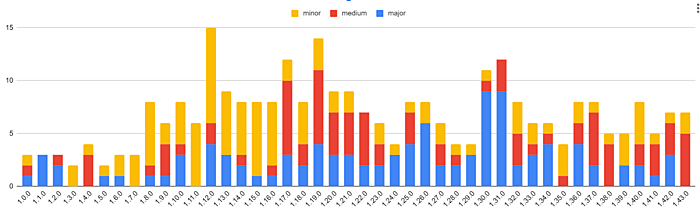

Here’s major/medium/minor:

There’s a peak around Rust 2018, and one from 1.12 to 1.19, but otherwise, it’s been pretty steady lately, in terms of overall changes. If we look at just major changes:

Rust 2018 had a huge bump. After 1.0, and after Rust 2018, it calmed. I think this chart is very interesting, and demonstrates the 3 year edition cycle well. We ship an edition, stuff calms down, things slowly build back up, we ship an edition, they calm down again.

So, why was my hypothesis wrong? I think this conclusion is fascinating. I think part of it has to do with my methodology, and that maybe, that difference explains some of the ways people feel about Rust. You see, even if we release extremely often, and a lot of releases don’t have a ton of changes in them (as you can see, it’s vaguely around 8 or 10, when you exclude the standard library, on average), the very fact that we do release often and have a decent, but fairly small amount of change means that things get into the release notes that may not if we had the exact same amount of change, but did yearly releases.

So for example, in 2019, we released Rust 1.32 to 1.40. That involved 35 language changes. Would I have included, say, “you can now use #[repr(align(N))] on enums” if I had been writing a post about all of these changes for the whole year? Probably not. But because there were only eight total changes in that release, with half of those being language changes, it made sense to include in the 1.37 release post.

Does this mean that folks who read the release posts and think Rust changes a lot are wrong? No, it does not. For those of us in the thick of it, a lot of the smaller changes kind of blur into the background. I actually initially typed “#[repr(N)] on enums” when writing the above sentence, because this change isn’t relevant to me or my work, and is pretty small, and makes things more orthogonal, and so it is just kind of vague background noise to me. But to someone who isn’t as in-tune with the language, it’s harder to know what’s big and what’s small. The endless release posts with tons of stuff in them makes it feel like a lot is happening. But the same amount of stuff may be happening in other languages too, you just don’t see them in release posts, because they only put out one once a year. You both see them less often, as well as see less in them.

I don’t think this means that the Rust project should change its release schedule, and I’m not entirely sure if this means we should change how we write release posts. However, maybe there’s a better way to surface “these are big changes” vs “this is a small thing,” or something like that. I’m not sure. But I do think this helps me understand the disconnect a lot better.

Issues and further research

There are some big issues with this methodology. No analysis is perfect, but I want to be fair, so I’m calling out all of the stuff I can think of, at least.

The first of which is, this is inherently subjective. There’s different degrees of subjectivity; for example, “total changes in the notes” is fairly objective. But not completely; folks have to decide what goes into the release notes themselves. So there’s already a layer of filtering going on, before I even started looking at the data. Doing this analysis took me two days of real time, but only a few hours of actual work. Something that analyses the git repo in an automated fashion may see other results. I argue that this level of subjectivity is okay, because we’re also testing something subjective. And I think I designed my methodology in a way that captures this appropriately. On some level, it doesn’t matter if the “real” answer is that Rust rarely changes: folks still get this info by reading the posts, and so I don’t think saying that “oh, yeah you feel that way, but this graph says your feelings are wrong” is really going to help this debate.

The second problem expands on this. We sort of had three eras of release note writing: the first few posts were written by Aaron and Niko. As of Rust 1.4, I took over, and wrote almost every post until 1.33. I then stepped back for a while, though I did help write the 1.42 post. The release team wrote 1.34 onward, and it was more of a collaborative effort than previous posts. This means that the person doing the filter from release notes -> blog post changed over time. This can mess with the numbers. For example, there are some blog posts where I would have maybe omitted a small family of features, but the folks writing that post included them all, individually. This may explain the uptick in language changes lately, and why many of them were not rated as “major.” Additionally, the people who did the filter from “list of PRs” to “release notes” also changed over time, so there’s some degree of filtering change there, as well.

To complicate things further, starting with Rust 1.34, Cargo lost its section in the release blog posts. Big changes in Cargo still made it into the text, but the previous posts had more robust Cargo sections, and so I feel like post-1.34, Cargo was under-counted a bit. Cargo changes are toolchain changes, and so the recent calm-ness of the toolchain numbers may be due to this. This still is okay, because again, this analysis is about folks reading the release notes, but it’s worth calling out. Likewise, I think the standards for writing the library stabilizations changed a bit over time too; it’s gone from more to less comprehensive and back again a few times.

This was mentioned above a bit, but for completeness, the structure of Rust releases means there’s a variable criteria for what makes it into a release post. If it’s a smaller release, smaller changes may get featured, whereas if those same feature were in a bigger release, they may not have been. I think this aspect is a significant factor in the rejection of my hypothesis, as I mentioned above.

I think there’s interesting future research to be done here. I initially tried to track deprecations and soundness fixes, but soundness fixes happened so little it wasn’t worth talking about. There were 7 in those 42 releases. This is another weakness / area for future research, because I did not include point releases, only 1.x.0 releases. This would have added a few more soundness fixes, but it also would have added a lot of random noise where not much happened in the graphs, so that’s why I left those out. They also don’t happen on the same regular schedule, so time would get a bit funny… anyway. Deprecations was also just hard to track because there weren’t a lot of them, and sometimes it was hard to say if something was deprecated because of a soundness issue vs other reasons.

Is my critera for adding syntax correct? I think a reasonable person could say “no.” If you have something that’s special cased, and you’re making it more general, there’s a good argument that this is removing a restriction, rather than adding a feature. But reasonable folks could also say you’ve added something. I don’t think that this part is core to my analysis, and so I think it’s fine that I’ve made this decision, but you may not care for this section of results if you disagree.

This analysis doesn’t get into something that I think is a huge deal: the ecosystem vs the language itself. I only track the Rust distribution itself here, but most Rust programmers use many, many ecosystem libraries. When people talk about churn in Rust, do they really mean the ecosystem, not the language? In some sense, doing so is correct: Rust having a small standard library means that you have to use external packages a lot. If those churn a lot, is it any better than churn in the language itself?

Does Rust have a small standard library? There were 962 changes in 42 releases, that’s almost 23 changes per release. A lot of them are small, but still. Maybe Rust has a small, but deep standard library? Due to coherence, I would maybe think this is true. Just how big are standard libraries anyway? I’ve only seen discussion of this concept in terms of design philosophy. I’ve never seen a numerical analysis of such. Is it out there? Do you know of one? I’d love to hear about it!

I think there’s a number of reasons that the standard library changes dominate the total change rate. Primarily, this section of the blog post tends to be the most complete, that is, out of the total amount of changes, more standard library changes make it into blog posts than other kinds of changes. Why? Well, it’s really easy to measure: count up stuff stabilized and put it in a big list in the post. It’s also about how these changes are measured; when a method is added to every number type, that’s u8 + u16 + u32 + u64 + u128 = 5 changes, even if conceptually it’s one change, in a different sense.

This leads to another question about those standard library changes: what is up with that weird peak around Rust 1.33? Well, we added the const fn feature in Rust 1.31. After that landed, we could const-ify a number of functions in the standard library. The initial huge bulk of changes here landed in 1.33. It had 138 changes, but only 13 were not “this function is now const.” And the feature continues to drive change outside of 1.33; the initial landing of const fn in 1.31 was very limited, and as it expands, more functions that already existed can be made const.

In conclusion, even though I still believe that Rust has slowed down its rate of change a lot, I think that it makes total sense that not everyone agrees with me. By some metrics, I am just flat-out wrong.