Deleuze for developers: assemblages

The ancient Greeks thought that atoms were it. ἄτομος, Wikipedia will tell you, comes from ‘ἀ’- meaning “not” and ‘τέμνω’, meaning ‘I cut.’ Cells are the smallest thing that there is. You can’t cut them in half. Everything is composed of a bunch of atoms.

Well, guess what? Modern science has found things smaller than atoms. Dammit! What we do know for sure, though, is that some things are made up of composites of other things. That’s for sure. We’re still not clear on what that fundamental stuff is, but composites are a pretty safe bet. Even if atoms are made up of other things, we know that other things are made up of a bunch of atoms.

So how can we talk about composites? Well, a programmer’s fundamental tool is abstraction. So we can black-box any particular composite and treat it as a whole entity, without worrying about what we’ve encapsulated inside. That’s good, and that’s useful, but there’s a problem: when you start thinking of a collection of things as just one thing, you miss out on a lot of important details. As we know, all abstractions are leaky, so how does a black box leak?

Let’s think about your body: it’s a composite, you’re made up of (among other things) a whole pile of organs, and one (skin) wrapping the rest of them up in a nice black box. If we had lived a few hundred years ago, thinking of the body as a black box would be a pretty fair metaphor: after all, if you take out someone’s heart, they die. The box needs all of its parts inside. Today, though, that’s not true: we can do heart transplants. Further, we have artificial hearts. A person with an artificial heart is not the exact same as a person without one, yet they are both still people. Thinking of a body as a totality leaks as an abstraction in modern times.

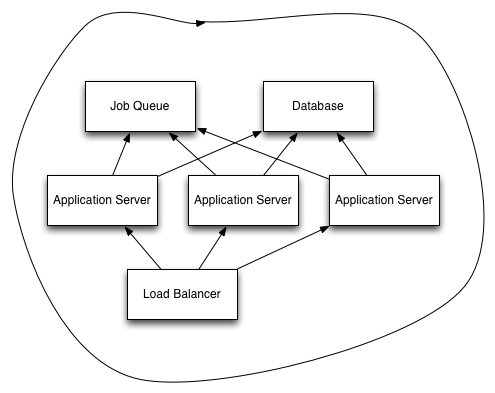

Let’s move away from biology for a bit and into web applications instead. Here’s an architecture diagram of a typical web service:

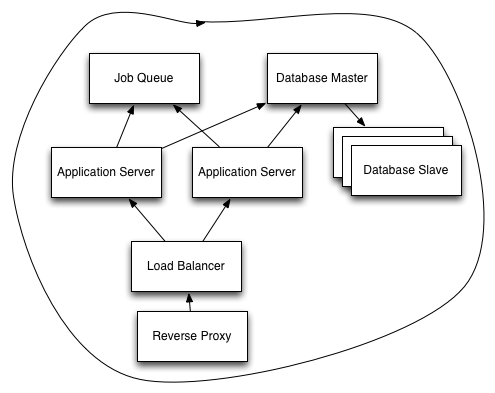

Looks pretty normal, right? Let’s modify it a bit:

This is the same web service, right? We’ve introduced a few database slaves and a reverse proxy, which allowed us to knock out one of our application servers. In a certain sense, this service is equivalent; in another, it’s different: It’s got another extra component, and one component has developed more complexity. We might need to hire a DBA and someone who’s good at writing Varnish configs. Different skills are needed.

So what do we call this thing? An ‘assemblage.’ It’s made up of smaller assemblages as well; after all, our application servers may use the Reactor pattern, the worker model of Unicorn, or the threaded model of the JVM. To quote Levi Bryant, “Assemblages are composed of heterogeneous elements or objects that enter into relations with one another.” In the body metaphor, these are organs, and in the systems diagram, they’re the application servers, databases, and job queues. Assemblages are also ‘objects’ in this context, so you can think of any of those objects as being made up of other ones. But to think of the formations of objects as a total whole or black box is incorrect, or at best, a leaky abstraction.

Let’s get at one other excellent example of an assemblage: the internet. Computers connect, disconnect, reconnect. They may be here one moment, gone the next, or stay for an extended period of time. The internet isn’t any less an internet when you close your laptop and remove it, nor when you add a new server onto your rack. Yet we still talk about it as though it were a whole. It’s not, exactly: it’s an assemblage.

Furthermore, there’s a reason that Bryant uses the generic ‘objects’ or ‘elements’ when talking about assemblages: objects can be ‘people’ or ‘ideas’ as well as physical parts. This is where the ‘systems’ idea of computer science diverges from ‘assemblage’: depending on how you want to analyze things, your users may be part of an assemblage diagram as well.

So what’s the point? Well, this is a basic term that can be used to think about problems. A design pattern of thought. A diagram. In future posts, I’ll actually use this pattern to address a particular problem, but you need to understand the pattern before you can understand how it’s used.

(and to give you a comparison of complexity of explanation, here’s the blog post by Levi Bryant on assemblages where I got that quote from. He quotes Deleuze directly and extensively: http://larvalsubjects.wordpress.com/2009/10/08/deleuze-on-assemblages/ )

The next article in the series is on ‘deterritorialization’.